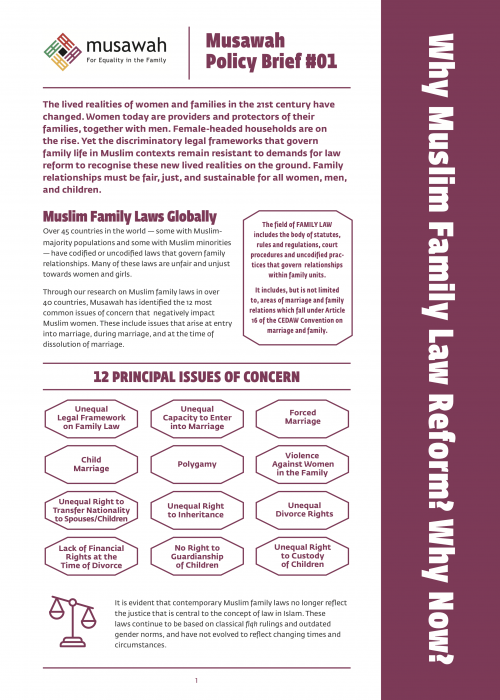

Why Muslim Family Law Reform? Why Now?

Lived realities of women and families in the 21st century have changed. Women today are providers and protectors of their

families, together with men. Female-headed households are

on the rise. And yet the discriminatory legal framework that

governs family life in Muslim contexts remains resistant to

demands for law reform to recognise these new lives realities

on the ground.

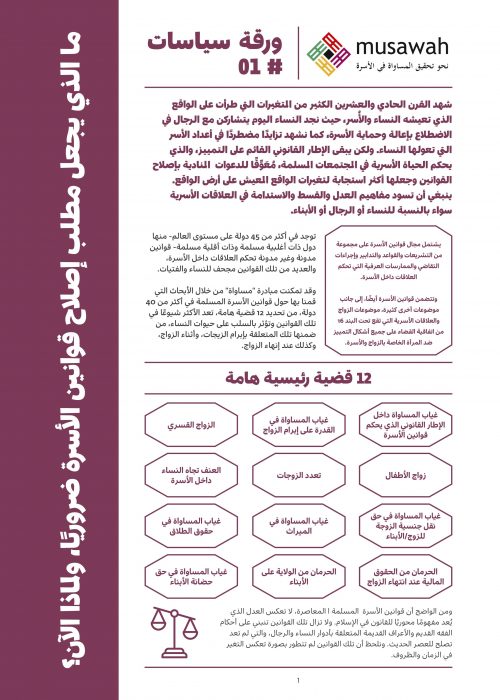

ورقة سياسات رقم 1

(العربية)

More than

Over 45 countries in the world – some with Muslim majority populations and some with Muslim minorities – have codified or uncodified laws that govern family relationships. Many of these laws are unfair and unjust towards women and girls.

More than

Through our research on Muslim family laws in over 40 countries, Musawah has identified the 12 most common issues of concern which negatively impact Muslim women. These include issues that arise upon entry into marriage, during marriage, and at the time of dissolution of marriage.

The field of FAMILY LAW includes the body of statutes, rules and regulations, court procedures and uncodified practices that govern relationships within family units. It includes, but is not limited to, areas of marriage and family relations which fall under Article 16 of the CEDAW Convention on marriage and family.

It is evident that contemporary Muslim family laws no longer reflect the justice that is central to the concept of law in Islam. These laws continue to be based on classical fiqh rulings and outdated gender norms, rather than contemporary notions of justice that include gender equality. Several arguments are commonly used to resist family law reform in Muslim contexts; these are often based on religious grounds. Many of those in authority claim that Muslim family laws are God-given and sacred, and therefore cannot be amended or reformed. Conservative religious scholars claim that men are the protectors and providers of their families and thus Muslim family laws must grant men authority and guardianship over women and children. They argue that any attempt to change such laws goes against Islam.

12 Principal Issues of Concern

Equality of Spouses in Marriage

Consent of Women

Capacity of Women to Enter into Marriage

Child Marriage

Polygamy

Violence Against Women in the Family

Nationality

Inheritance

Divorce Rights

Financial Rights at the Time of Divorce

Guardianship of Children

Custody of Children

However, over the past decades, scholarship and activism in the Muslim world have developed to make the case for the possibility and necessity of reform. Here are ten fundamental facts which demonstrate that resistance to reform of Muslim family laws is baseless and reform can and must happen.

Ten Fundamental Facts: About Reform of Muslim Family Laws

Many Muslim family laws treat women as minors under perpetual male guardianship. This means that key decisions pertaining to education, employment, livelihood, travel, marriage, birth control and spacing of children, etc., are determined by male guardians rather than women themselves. Such laws deny women full agency and autonomy on matters that impact their lives. Women and children are put in vulnerable socio-economic situations by laws that fail to protect their rights. The effects of discriminatory family laws and practices, as well as court systems and procedures which limit women’s access to justice, also contribute to poor mental health and other psychosocial impacts on women and children, effectively diminishing their quality of life.

Classical scholars defined marriage based on a contract of exchange: the wife’s obedience and submission in return for maintenance and protection from the husband. This legal framework still underpins Muslim family laws today, resulting in provisions, procedures, and practices that discriminate against women.

Lived realities of Muslim families are changing globally. Many women are heads of households, primary breadwinners, and main guardians of their children, or share equal roles with their partners. Many men are unable to fulfil their traditionally assigned roles of provider and protector. Yet, they continue to enjoy the powers and legal privileges, while women who take on responsibilities to support and protect their families are denied the corollary rights. In fact, regardless of circumstances and roles within families, women continue to be treated as perpetual minors by law and in practice.

Today’s Muslim family laws were written and enacted by governments based on a combination of classical fiqh (or centuries-old human interpretations of the Shari‘ah), local culture, and colonial heritage. There is a clear difference between Shari‘ah and fiqh. While Shari‘ah is considered divine and eternal in Muslim belief, fiqh consists of human-made interpretations from a specific time and place, and is therefore changeable.

Fiqh rulings are divided into two categories:

(1) ‘ibadat, devotional and spiritual acts related to relations between God and the believer; and

(2) Mu’amalat, social and contractual acts among humans.

Rulings in the latter category, which include marriage and family matters, have always been considered open to change based on changing circumstances. Family laws are not sacred; they are human-made.

Discriminatory family laws and resulting injustices contradict the guiding ethical principles of the Qur’an, as well as contemporary notions of justice and human rights principles. In fact, the main sources of Shari‘ah—the Qur’an and Sunnah—promote human and marital relations that embody equality, justice, love, compassion, and mutual respect between individuals.

For instance, Surah an-Nisa’ 4:21 depicts marriage as a ‘solemn covenant’ (mithaq ghaliz), with mithaq derived from thiqa (trust). Marriage is seen as an intimate and serene union in Surah al-Baqarah 2:187 (‘They are your garments and ye are their garments’) and Surah ar-Rum 30:21 (‘God created for you mates from among ourselves, that you may dwell in tranquillity with them, and God has put love and mercy (mawaddah wa rahmah) between your (hearts)’).

Family laws that are developed or amended in the name of Islam should reflect the Qur’anic values of justice (‘adl), equality (musawah), equity (insaf), human dignity (karamah), love and compassion (mawaddah wa rahmah), and mutual respect among all human beings. All these values are fully compatible with international human rights standards, including CEDAW, and national constitutional guarantees of equality and non-discrimination.

Muslim legal tradition is rich, flexible, and dynamic. It provides the conceptual tools and legal methods to guide a shift towards egalitarian gender relations in families and society. These include:

- IJTIHAD (lit. endeavour, self-exertion) Denotes human efforts to understand and interpret the Shari‘ah in order to find solutions to existing and emerging problems.

- IKHTILAF (lit. disagreement, difference) Refers to diversity of opinion among jurists that existed since jurists first attempted to interpret the Qur’an and Sunnah. Difference of opinion was very much a part of the rigour of Muslim legal tradition.

- MASLAHAH (lit. benefit or interest) Allows for reform of rules, laws, and practices to benefit society and meet the changing needs and interests of Muslim communities.

- DARURAH (lit. overriding necessity) Principle that recognises new and urgent situations and allows for legal flexibility in order to avoid serious harm.

- ISTIHSAN (lit. judicial discretion) and ISTISLAH (lit. to deem proper) Allows for the formulation of rulings and laws based on what is seen as the better solution for individuals and communities

There is no such thing as one divine ‘Muslim family law’ for all Muslims globally and eternally. Muslim family laws were influenced heavily by historical events, local customs, and norms, as well as legal and social values introduced in different periods of history, including during the colonial era. In fact, many of the present-day Muslim family laws are colonial legacy laws. The diversity of Muslim family laws is evidence of the role that humans have played in developing these laws and how changeable and adaptable these laws can be.

Muslim family laws around the world are in a constant state of evolution and have been changing according to the shifting realities of time and place. Recent reforms in Muslim family laws towards equality and justice show that change is indeed possible with the political will of state leaders and policy makers.

Several Muslim-majority countries have reformed their family laws using an Islamic framework and building on core Qur’anic principles of equality and justice. Such reforms include:

Algeria: The Family Code requires each spouse to: (i) cohabitate in harmony, mutual respect, and kindness; (ii) contribute jointly to the preservation of the family’s interests, the protection of their children, and the provision of a sound education for them; and (iii) mutually agree in the management of the family’s affairs, including the spacing of births.

Morocco: The Family Code (Moudawana) recognises marriage as a partnership of equals and specifies the ‘mutual rights and duties’ between spouses, which include: (i) cohabitation, mutual respect, affection, and the preservation of the family interest; (ii) both spouses assuming the responsibility of managing and protecting household affairs and the children’s education; and (iii) consultation on decisions concerning the management of family affairs.

Global surveys on gender equality (WEF, Global Gender Gap Index 2020) reveal that up to 21 countries in the bottom 25 are Muslim-majority countries. Family laws and practices are connected with all aspects of women’s lives. It is impossible for women to make key decisions pertaining to education, employment, and livelihood without full autonomy in marriage, and equal rights to divorce, inheritance, and nationality.

Equal opportunities in getting a job or starting a business do not exist where legal gender differences are prevalent. Legal restrictions constrain women’s ability to make economic decisions and can have far-reaching consequences.

Global data show that more women join the workforce overall in economies that are reforming towards gender equality (World Bank, Women, Business and the Law Report 2019). Family laws and other laws (e.g. labour laws) governing these areas are intertwined, so reform of discriminatory family laws is a prerequisite for achieving gender equality.

Governments bear the primary responsibility for implementing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which have been endorsed internationally as critical goals to address inequalities and human development gaps. In addition to Goal 5 on ‘Achieving gender equality and empowering all women and girls,’ reform of family laws also impacts progress on other SDG goals such as Goal 3 on ‘Ensuring healthy lives and promote well-being,’ Goal 4 on ‘Ensuring inclusive and equitable quality education for all,’ and Goal 8 on ‘Promoting economic growth, full employment and decent work for all.’

Recent studies have found that ‘egalitarian reform of family law is one of the most crucial pre-conditions for empowering women economically’ (Htun, et al., 2019), and that gender equality benefits national and global economies, and society in general (McKinsey Global Institute, 2015).

Families, in all their diversities and forms, are at the core of all societies. Families can be both a central support system and a place where individuals experience exploitation and discrimination. Egalitarian family laws foster an environment where family members support one another based on who is best able to do the task at hand, and not on gendered roles.

Musawah advocates for substantive and transformative approaches to equality: gender-sensitive laws, policies, and programmes that correct women’s social and historical disadvantages, with the goal of long-term transformation of institutions, systems, and power relations.

States, religious leaders, civil society, and community organisations must ensure that women have meaningful decision-making power; are full participants in family, society, and state; and are able to enjoy dignity, security, and respect.

Family laws that discriminate against women in the name of religion are no longer acceptable. Reform of Muslim family laws is both necessary and possible. In the 21st century, there can be no justice without equality

Resources Cited

Zainah Anwar, ed. 2009. Wanted: Equality and Justice in the Muslim Family. Petaling Jaya: Sisters in Islam. Available at: https://www.musawah.org/resources/wanted-equality-and-justice-in-the-muslim-family-en/

Mala Htun, Francesca R. Jensenius, and Jami Nelson Nuñez. 2019. ‘Gender-Discriminatory Laws and Women’s Economic Agency’. Social Politics 26:2, pp. 193–222. Available at: https://academic.oup.com/sp/article/26/2/193/5303946

McKinsey Global Institute. 2015. The Power of Parity: How Advancing Women’s Equality Can Add $12 Trillion to Global Growth. Available at: https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/employment-and-growth/how-advancing-womens-equality-can-add-12-trillion-to-global-growth

Ziba Mir-Hosseini, Mulki Al-Sharmani, and Jana Rumminger, eds. 2015. Men in Charge? Rethinking Authority in Muslim Legal Tradition. Oneworld: London.

Musawah. 2009. Framework for Action. Petaling Jaya: Sisters in Islam. Available at: https://www.musawah.org/resources/musawah-framework-for-action/

Musawah. 2016. Musawah Vision for the Family. Available at: https://www.musawah.org/resources/musawah-vision-for-the-family/

World Bank, Women, Business and Law Report 2019. Available at:

https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/31327

World Economic Forum, Global Gender Gap Report 2020. Available at:

https://www.weforum.org/reports/gender-gap-2020-report-100-years-pay-equality